Vexed in Venice

With an enormous quantity of work on show, the 2022 Venice Art Biennale rests its bona fides on scale and technical trickery. But the end result is one big empty gesture

Click here to listen to an audio version of this piece, read by the author.

“When people tell me they don't understand a work I say: ‘Fine, just look to it. The confrontation is part of its power.’ Don't vex yourself with an intellectual understanding of it. The body knows things way before the brain does.” Thus Ugo Rondinone, artist, multidisciplinarian extraordinaire, one of contemporary art’s most bankable names, in an interview from the June 2022 issue of the bilingual monthly journal ArtPress. That I read the Rondinone interview while on the plane home from Venice, where I’d spent four days deriving all I could from the 2022 Biennale, can surely only be considered a kind of prophetic sign on my part. The words on the page, supposedly having exited Rondinone’s mouth, left me just as breathless as the art had. How dire the situation appeared to me on that plane ride back; how endless was the view from here towards the art of the future which, it seemed then and still seems now, will surely resemble to an almost indistinguishable degree the art of today.

Contemporary art simply lacks. It lacks new ideas, it lacks depth, but most pressingly of all, it lacks a sense of communicability. Rondinone’s babbling interview would have been proof enough, but this year’s Venice Biennale is an undeniably more complete illustration. The Biennale exhibition, entitled The Milk of Dreams (Il latte dei sogni), is a fusion of past and future. Curator Cecilia Alemani has crafted a catalogue comprised almost entirely of women artists, almost half of whom are no longer alive. The exhibition thus becomes a summoning forth from the dungeons of 20th century art the many overlooked, the many forgotten, as well as an active attempt to ensure, for those contemporary artists whose work was chosen for the Biennale, that their fate play out differently. This, in one sense, is the Biennale’s principal theme. But Alemani is also concerned with dream worlds, as the title suggests. Dream worlds, exotic mysticism, nature worship. Dean Kissick, in his review of the exhibition for Spike, was quick to note the well-wornness.

Dream logic was fashionable for artists 110 years ago; it remains, in less experimental and somewhat more insistent ways, a preoccupation for artists today. But then, of course it does. In one way, dream logic is the archetypal subject matter of our time, for it lays a set of ground rules perfectly convening to what today’s artists consider their occupational duty. Put plainly, dream logic offers a kind of apologia for art more or less empty in content but rich in technique. Encouraged to deploy a subjective, “subconscious” symbolism, artists no longer concern themselves with the communicability of content. Instead, a dialogue between artist and viewer must be achieved through other means.

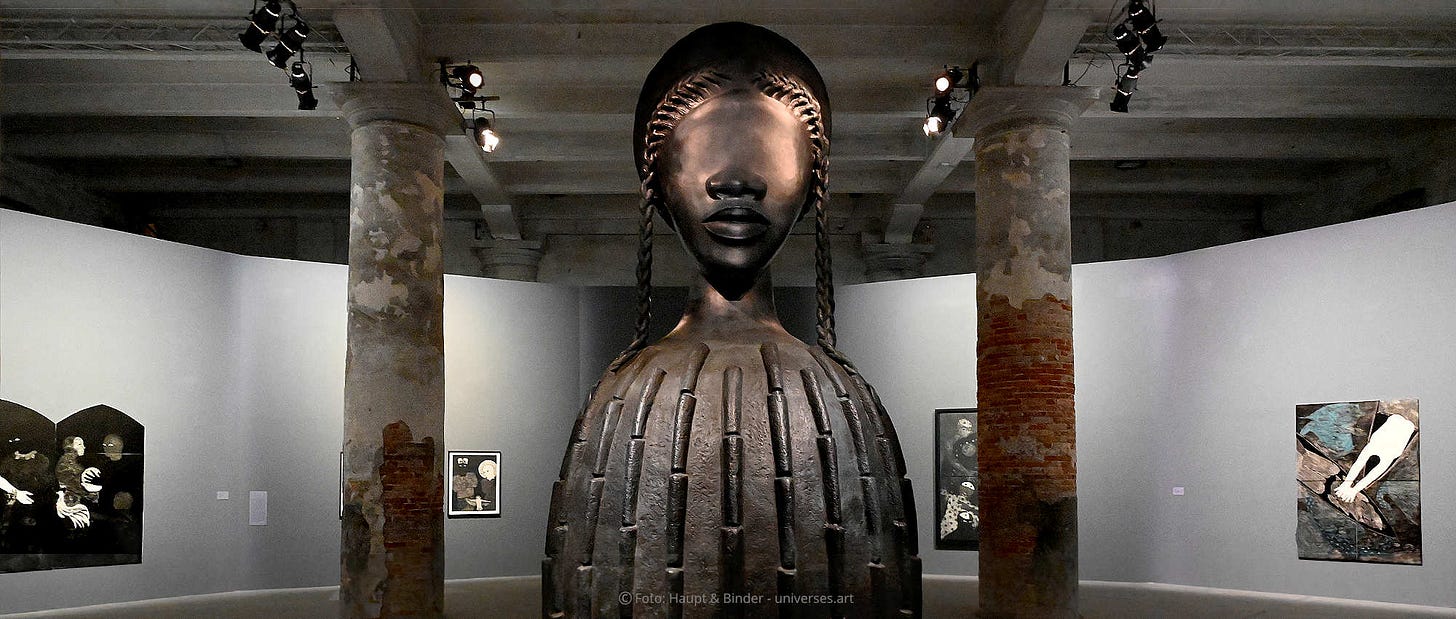

Technical proficiency is one such way, and thus we arrive at a situation where art attempts to win you over by sheer force of technique alone. The two sculptures which open the Arsenale and Giardini halves of the exhibition – respectively, Simone Leigh’s monumental Brick House from 2019 and Katharina Fritsch’s polyester elephant from 1987 – are attempts to do just that. Their monumentality is their point. Both artists hope that the questioning ends there. Prabhakar Pachpute’s ten-metre-wide mural, Delcy Morelos’s manmade soil maze, Sandra Mujinga’s room awash in green neon light – much the same.

Elsewhere, contemporary art’s unhealthy obsession with the multidisciplinary continues to prevail, as if this too were enough to sway a viewer’s judgment. Everyone seems to be combining forms nowadays. Chun Kwang Young’s Times Reimagined, held in the Palazzo Contarini Polignac, deems it necessary to mix sculpture, painting, architecture, design, and sound, in order to fully explore that most unexamined of themes – the effects of technological advancement on biological evolution and human nature. Here an irregularly beating heart thudding away, there a bright-red virus-shaped sculpture – put it in as many forms as you want, but it all amounts to the same tired critique. Kwang Young’s large-scale sculptures are constructed using hand-made hanji, a Korean paper derived from mulberry trees and made to last for 1300 years. Pages from a number of 19th-century Korean books which Kwang Young collected are torn out, folded into little triangles, and stuck together in the shape of biological deformities. The end result lies somewhere between aesthetic conviction and historical desecration. Modern recycling aesthetics here reach a kind of apotheosis, the beautiful past quite literally consumed for the sake of present-day art.

Yet when all of this fails – when the sleight of hand confuses, when the scale tires the eyes, when the element of multidisciplinary novelty falls flat, when, in short, nothing of consequence is communicated to the viewer – there’s always the option of simply telling us what you meant. The Milk of Dreams contains an inordinate amount of expository words. Take the description accompanying Kwang Young’s exhibition: “His message in this project is very clear and decisive. He suggests that now is the time for all of us to act…” Yawn.

This is actually a somewhat tame quotation in what is otherwise a festival of inanity. Everywhere, nonsense art-speak appears with a total lack of self-consciousness, terms like “aesthetically relational” and “cosmologies” and “spatialised progression” bandied about without issue. In Lithuanian artist Eglė Budvytytė’s film Songs from the Compost: mutating bodies, imploding stars, images of dancers writhing and turning in a Lithuanian forest play out while a narrator with a Justin Vernon-style voice transmogrification sighs: “I’m a ghost, I’m a host, I’m being hosted, I’m a host, I’m a ghost, I’m being ghosted, I’m being a host, I’m hosting snakes in my head… A crack in the rock, a crack in the narrative, a crack in history.” Walking off from this section of the exhibition, I saw the woman next to me holding her fingers in her ears.

But then, doesn’t this necessity to explain fly in the face of Rondinone’s supposed empiricism? Aren’t we no longer in the realm of feeling your way towards an understanding of the work, trapped instead in a desire that everything be unambiguously explained to us? Aren’t we perhaps straining to avoid the harsher consequences of Rondinone’s aforementioned “confrontation”? All pertinent questions, and all dismissible. The issue, at its core, is perennial, and deserves the attention of bigger minds than Ugo Rondinone. “Nay, but I’ll tell not all that I saw then; / The long theme drives me hard, and everywhere / The wondrous truth outstrips my staggering pen.” Thus wrote Dante, in the fourth canto of Inferno. Numerous are the occasions in his Divine Comedy in which the temptation to describe is forsaken. With an unmissable irony, the great poet knew that there is a certain kind of beauty which words can only diminish. Which is why he called for the recognition of an artistry beyond words – a call today’s practitioners would do well to heed. From the end of Paradiso: “Now in her beauty’s wake my song can thrust / Its following flight no farther; I give o’er / As, at his art’s end, every artist must.”

But I wasn’t at the Biennale to indulge in misanthropy. I was at the Biennale because I wanted to feel good. I wanted to forge new encounters, discover artists whose intuitions for beauty left me clamouring for more. In her essay ‘One Culture and the New Sensibility,’ Susan Sontag expresses a belief that “the purpose of art is always, ultimately, to give pleasure – though our sensibilities may take time to catch up with the forms of pleasure that art in a given time may offer.” And perhaps it’s simply an antiquated sensibility that I carry around with me, preventing me from connecting with today’s art. Except that I was indeed able to find pleasure in much of what The Milk of Dreams had to offer, and by no means solely from artists of the past. Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, a 29-year-old Zimbabwean painter, is featured in the Venice Biennale for a second time this year. Her work oscillates with a kind of love-energy that is simply undeniable, expressed through harshly struck colours, disjunctions in tone, contrasting shapes, and a style of brushwork that one can only call free-associative. Her installation for The Milk of Dreams is a tender dedication to memory, paintings deeply rooted in the mystical traditions of the Shona. She is one of contemporary art’s most striking, sincere, and moving talents.

On the other end of the legacy scale is 92-year-old Ibrahim al-Salahi, a Sudanese-born modernist whose work is held in the collections at MoMa and the Tate. His drawings for the 2022 Biennale are perhaps the work of an artist no longer quite vigorous enough to accomplish the masterpieces of his earlier years. Yet their measured abstractness, their bustling rhythm, and above all their sense of humour, combine to make up for any shortcomings in ambition. Sketches which are small in scale yet nonetheless potent, and accomplished with a technical mastery that puts much of what is hung around them to shame.

These, along with the work of the late Belkis Ayón, are the standouts of The Milk of Dreams. Yet the pleasure I experienced strolling through the main exhibition was rather diminutive compared to that of inspecting the numerous national pavilions in the Giardini. The German Pavilion, formerly the Bavarian Pavilion, was remodelled and recast by the Nazis in 1938. It now resembles a starch-white altar to Fascist neoclassicism. Artist Maria Eichhorn has, in 2022, torn away the plaster, removed walls, quite literally dug up the building’s foundations so as to reveal its original passageways and layout. The result is not merely a rebirth of the Bavarian Pavilion – it is a testament to the immutability of history, and it is undeniably moving.

So too is the film, and accompanying interior, created for the French Pavilion by visual artist Zineb Sedira. Her film, at heart an exploration of how cinema can realise our nascent identities, features Sedira re-enacting moments from her past using prefabricated replicas of her former residences and hangouts. Viewers are then able to exit the screening room and stroll through a number of these very same sets – her living room, a film editing studio, a 1960s-style Algerian café. The past becomes inhabitable. It’s a dynamic and cohesive experience, fully satisfying on every level: emotional, cerebral, and aesthetic.

Yes, pleasure there is to be had after all. I required none of Sontag’s catching-up to be won over by al-Salahi, or Eichhorn or Hwami or Sedira. But then, neither is Sontag quite finished there. After defining art in terms of pleasure-giving, she continues: “And, one can also say that, balancing the ostensible anti-hedonism of serious contemporary art, the modern sensibility is more involved with pleasure in the familiar sense than ever. Because the new sensibility demands less ‘content’ in art, and is more open to the pleasures of ‘form’ and style, it is also less snobbish, less moralistic – in that it does not demand that pleasure in art necessarily be associated with edification.” This, I believe, is where she strays. Sontag’s gross miscalculation was not so much in failing to recognise the hollowing out of the more reliable, time-tested structures of meaning-making – this she well and truly understood. What she did not foresee, rather, was how the arts might become a stand-in for not merely the aesthetic sensibility of an age but its political and sociocultural aspirations too.

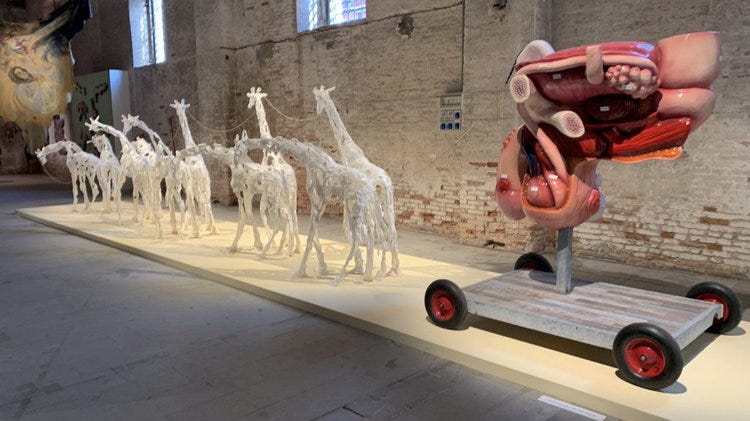

Ours is undoubtedly a moralistic epoch, and much of its art reflects that. Here Sontag was wrong. It is also a crass age, and my overarching conclusion was that this year’s Venice Biennale was an exhibition of wilful crassness. Everywhere we see piss and shit, menstruating vaginas, demonic eyes, body hair pasted onto canvas. One of the exhibition’s supposed showpieces is a large sculpture by German artist Raphaela Vogel, in which a giant illness-afflicted penis (quite literally warts and all) charioteers a steed of gaunt giraffes cast in a gooey-white mould and attached to the penis’ urethra by a golden chain. The end result is something so cheap, so vulgar, so simplistic, and so indescribably lame, that if it weren’t also so impossibly transparent you might be willing to dismiss it as ineffective satire.

Indeed, staring at Vogel’s work, mouth agape, I couldn’t help but wonder whether this was the key to something. Perhaps the perceived emptiness of contemporary art is a function of the emptiness of its symbolism. Symbols, after all, are a shorthand. They act as a bridge, inviting a viewer into a work, bringing a human concept to the point of comprehension. On the broader scale, symbols represent a shared reality. So it’s no surprise that much of the Biennale’s best art attempts, in a matter of words, to meet the audience half way. Luiz Roque’s short film Urubu, captured on Super 8 during one of São Paulo’s COVID lockdowns, consists of nothing more than a twenty-second shot of an aruba flight. The bird floats around, weaving through an anonymous block of apartment towers. That’s all. Twenty seconds and it’s over. But we know that nothing more is needed, because we find no superfluous elements interrupting the line connecting artist, symbol, and viewer. Anyone who experienced a lockdown can recognise something familiar in the free flight of that bird.

Think then of a giant, chain-sprouting, genital-wart-encrusted penis. You oughtn’t need to strain your mind to see with some clarity where things sit. “Just look to it,” insists Ugo Rondinone. He’s on the right track. Representational art shouldn’t primarily be judged according to the newness of its ideas. More important is the degree to which it can incite an emotional reaction within a viewer. This year in Venice, however, we find a collection of art professing an idea-centric worldview. It foregoes symbolic depth for a supposed depth of ideas, insisting on being “about something”. Its unmissable sense of insecurity begs for our attention. So we look to it – perhaps out of curiosity, or perhaps pity. We look and we look and we look. But what are we to do when our eyes lead only onto blank objects? What do we do when there is no there there? I suppose we walk fifteen minutes to Peggy Guggenheim’s villa. There we can see the de Chirico’s. No intellectual understanding needed – just pure pleasure.